Wild Botswana

There’s an art to standing at the back of an 18ft narrow canoe and using a long thin pole to push it forward, so our guide tells us in the Okavango Delta as we glide down a small tributary looking for wildlife. You have to steer and push at the same time and make sure the pole doesn’t get stuck in the soft mud. I’m told it takes time to learn. As we float serenely along we see some hippos taking a breath, so our guide gently turns the dugout canoe around and we head back to where we started, passing water lillies and birdlife along the way. After we moor up, I ask our guide if I can have a go. He laughs as he starts to put the pole away, but his face hardens when he realises I’m serious. He looks at me with a combination of skepticism and concern, saying it took him three years to learn. What he doesn’t know is that I’ve done this before, or at least something very similar. In Oxford, punting down the River Isis with a jug of Pimms and punnet of strawberry’s is like taking a daily stroll in the park.

The guides standing at the side of the river look on nervously as I take the long pole in my hand and push the 2ft wide canoe out into the water. They’re surprised to find my wife, Jess, is happy to sit in the canoe whilst we roll this dice in water containing hippos and crocodiles. But I’ve been punting many times over the last 15 years, and whilst their ‘Mokoro’s’ are much thinner and a lot more unstable, the principle is the same. Finally, at long last, the rather ludicrous local pastime of the people of Oxfordshire has come in useful. We take the Mokoro up and down the river for a few hundred meters whilst the guides walk tentatively along the adjacent bank. It’s one of those rare moments where a skill you considered largely useless has come to impress others. Back on land, I’m quickly offered a job.

(Punting the Okavango Delta in a Mokoro canoe, Botswana)

We entered Botswana by car from its western border with Namibia the week before. Our first stop will be in the town of Maun, a five hour drive north-east from the Charles Hill border post. The journey begins to pass relatively uneventfully in the 4×4 we rented in Namibia. Thankfully, the border crossing was a breeze. The only issue was not being able to take my recently bought strawberries over the border. I sit and force-feed myself the whole punnet whilst scowling at the border guard.

The differences between Namibia and Botswana are subtle. The fences that predominated the roadsides of our 5000km drive through Namibia have rapidly dropped away. Secondly, and sadly, there appears to be a bit more plastic rubbish, perhaps reflecting the significant efforts in Namibia to ban single use plastics in recent years. Thirdly, all of their waste bins, which are made from old oil drums, are painted the colours of the nations flag (sky blue with a black and white central stripe). It’s a nice touch, providing a sense of national identity as you drive along. Finally, and it’s hard to ignore, it’s hot, and as we head further north-east it seems to be getting hotter. With little to no wind, I think I might struggle in Botswana.

The lack of fences as we drive along makes the scenery feel more open. You feel less penned in than in parts of Namibia. But as a result there’s an increased number of dead animals at the roadside. We saw none in three weeks of driving in Namibia, but here we see a dead cow within the first hour. It also means the speed limits are lower, regularly 80kph for significant stretches. That doesn’t stop you having to occasionally slam on your brakes for suicidal goats, but it makes for slightly shorter skid marks.

As we drive on we see mainly farm animals, but not a lot else. The bush is head-height, dry, thorny and dense beyond the strimmed roadside. As we travel further north towards the small town of Ghanzi the road becomes fence lined and I’m reminded of the small villages we regularly came across in Uganda. The only difference here is that not every other building is selling something. Fruit, vegetables, drinks, kitchen sinks, beds, you could get it all in every town of Uganda, but here the population density is unable to support the same level of entrepreneurial commerce. I also get the impression that this western section of Botswana attracts relatively little tourism. It’s not surprising, it’s mainly dense and untamed farmland, with any significant towns hundreds of kilometres apart.

We drive on and Jess starts a game of ‘I Spy’. It fizzles out as quickly as it started. She guessed my R was ‘road’. As we exit the Ghanzi district, the fences disappear again. We make our way east towards the town of Maun, which sits at the southern edge of the Okavango Delta. Since I was about 15 I have wanted to visit the delta. I vividly remember a National Geographic documentary where the cameraman was flying over the water covered delta in a helicopter. The zebra and impala were grazing on the grass or bouncing through its shallow waters. As we drive into the rather disparate and uninspiring town of Maun these memories make me desperate to get into the delta itself.

(Reeds at sunset on a tributary of the Okavango Delta, Botswana)

The Okavango Delta is a true wonder of nature. It’s the largest inland delta on the planet, covering an area of approximately 15,000sq/km. Each year heavy rainfall from Angola travels south and floods the entire area, providing one the greatest wildlife spectacles on the planet. The dramatic change in seasonal flooding has also thankfully made human colonisation of the delta challenging. The result is a relatively untouched and pristine natural environment where predator and prey can live in continual combative harmony.

For our safari into the delta we originally planned to just turn up and bootstrap something together. I’m glad we didn’t, the town of Maun doesn’t really feel like it has any obvious centre and I think trying to assemble a trip from here would have been challenging. Not impossible, but difficult. The delta is, unsurprisingly, in a constant state of change, so driving any great distance across it is not for the faint hearted. As a result, just before arriving in Botswana, we booked a last minute 5 day guided tour. It includes three short internal flights which connect us to two camps in the delta’s centre.

Our first flight is to a camp called Rra Dinara, which translates to male buffalo. The flight is in a small plane with 15 seats, but nobody else is on it other than the pilot. From the air you can see the winding paths of the delta’s various tributaries, but it’s dry season so the grasses are dry and the water level is low. Occasionally, you can see small herds of elephants and antelope as clustered black dots as we fly over. As we approach the landing strip, a parched stretch of bush that’s been cleared and graded, we do a full circle to make sure there’s no animals on the runway.

(View of the Okavango Delta from the air, Botswana)

Once we’re off the plane we’re driven to our camp via a series of dirt tracks winding through the delta, it’s surprisingly dry and barren, with scorched trees along the roadsides. Four ladies greet us at the camp by singing and handing out cold towels. It’s oppressively hot, around 38-40 degrees Celsius and no wind. My iPhone complains that it’s too hot, even in the shade. The camp itself is a series of raised green ‘safari tents’ accessed via a wooden walkway. The main restaurant and bar are made from wood with an unobstructed view out onto a stretch of river. Within the first few hours we’ve seen water buffalo, impala, white egrets, fish eagles, giraffe, elephant, warthogs, zebra, and secretary birds, just from sitting playing cards looking out from our tent or drinking a beer by the pool.

(Jess enjoys a pool safari at Rra Dinara, Okavango Delta, Botswana)

By early afternoon we’ve met our safari guides for the next two days, Lake and Mark. They suggest we go out for an afternoon game drive coupled with a brief night game drive on the way back, something we haven’t done before. As we leave the camp at 2pm they explain that they saw two leopards earlier that day and want to know if we want to try and find them again. We nod enthusiastically and after half an hour we arrive at the spot, but there’s no leopards in sight. We drive off the road and into the bushland (something you can only do in private conservancy’s, unlike the Masai Mara and Serengeti) and Mark puts a closed fist up into the air. I’ve seen enough Stallone and Schwarzenegger films to know that means shut up. A faint groan can be heard somewhere behind us. They turn the car and we creep on. After a few hundred meters we find them, a male and female leopard on the ground. The female is lying in front of the male, flicking him in the face with her tail. The male ignores it for a while, then seemingly out of annoyance, he climbs on top of her and they mate for all of about 20 seconds. He bites her on the back of the neck to seal the deal and they separate whilst growling loudly. It’s an amazing sight, and something we didn’t expect to see. After countless safaris we’ve only seen two individual leopards lazing in trees. After a few minutes, the male finds himself some shade and slumps down after his Herculean efforts. Then the female gets up, plonks herself down in front of him and starts flicking her tail in his face again. After a few minutes of frustration the male repeats his obligations in the 38 degree heat. This happens once more before we leave them in peace. Another jeep has also arrived, and the Botswanan government has placed strict rules on how many cars can be present at any one time. In a rare moment like this, only one car is allowed.

(A post-coital male leopard stares to camera, Okavango Delta, Botswana)

We head off in search of African Wild Dogs, an endangered species that’s been high on our list to see. As we drive along, Lake and Mark start talking about the ‘Fresh Prince’. I am utterly confused about why they would be discussing a 1990’s Will Smith comedy show in the middle of the Okavango Delta. I think for a moment and then, dumbfounded, I ask Jess. She smiles at me like you might at a small child and says “no darling, fresh prints”. I’m so glad I didn’t ask Mark or Lake.

After driving through a forest of Mopane trees, all of which have been stripped bare and had their branches snapped by elephants, we make our way onto an open dusty plain. After our guides have checked the ground for prints rather than Will Smith, they find a group of five puppies playing near a hole in the ground. We don’t see any adults and the park rangers we meet later are concerned that they might have been abandoned. We wait patiently for an hour, but there are no signs of the parents. We leave as the large red sun is setting in the distance, then stop just before it disappears for a sundowner drink. Once it’s dark, the guides bring out the large torches and we drive back scanning the savanna for the red eyes of nighttime predators. We see a porcupine waddling its way along and a large spotted genet hiding in a tree.

(Endangered African Wild Dog puppies wait for their parents return in the Okavango Delta, Botswana)

The next morning we wake at 5:30 am and head out on safari. Not far from the camp our guides stop the car. They exchange a few words, then point to a footprint and say to us “lion, female, passed by this morning”. How they can tell this is beyond me. The print looks like a smudge in the powdery dirt. We’ve seen similar skills in a few other national parks in Africa, but here it rises to a new level. Their ability to track is second to none. Throughout the day these skills prove themselves over and over again as we see a wide variety of animals; a large pack of wild dogs (the puppies had not been abandoned), numerous elephants, zebra, a warthog that looks like it’s wearing high heels, the list is endless.

(An endangered adult female African Wild Dog shows its teeth when yawning in the morning, Okavango Delta, Botswana)

(A Warthog poses for camera, looking like it’s wearing high heels, Okavango Delta, Botswana)

But it’s in the afternoon that we get a real surprise. We find four male cheetahs all strolling along, their bellies full having clearly eaten recently. We track them through the bush and eventually they find a large section of water at which to drink. We pull up the car and watch as the sun is setting over the rippling delta. Behind us two elephants are wading gently through the water, their legs creating a swooshing sound as they wander. The scene is utterly beautiful, calming and peaceful. With the sunset reflecting off the water you feel a true sense of freedom and isolation, away from the madness of modern living. Mark, one of our guides, holds his fingers up to the sun to calculate the time to darkness. We leave the cheetahs drinking and head to a quiet open spot for a drink ourselves.

(Three male cheetahs search for water after a full meal, Okavango Delta, Botswana)

(A male cheetah at sunset, Okavango Delta, Botswana)

Over a beer on an open grass plain at dusk we chat to Mark and Lake. The latter mentions that he has a relatively new born child. I ask how it works with his wife going into labour and them working 3 months in the delta and then 3 weeks off at home. The only way out is by plane. He looks at me confused. He then explains that the last thing he would ever want to do is to be there for the actual birth. Now it’s my turn to look confused. Both Mark and Lake then explain that in Botswana it is rude, perhaps even disgusting, if a father were to be involved in the birthing process. They typically will not see their new born child for at least 3 weeks after birth, sometimes it can be as long as 3 months. Either the father moves out of the house, or the expectant mother moves in with her mother to give birth. When we say it’s common in the U.K. for the father to be present at the birth they physically recoil, looking at me with horror. I tell them that I’m not entirely sure I dislike the Botswanan approach.

The next morning we say goodbye to Mark and Lake and board another tiny aircraft to our next destination, Moremi Crossings. As we wait I admire the airport amenities, a spinal board and two fire extinguishers in an open sided wooden shed. The tiny plane touches down in a plume of dust. As we climb onboard another passenger asks us if we are likely to be sick. What a strange question I think to myself. She then says the last passengers in our seats were both sick, so the sick bags have gone. As the plane takes off and the thermal updrafts of the midday heat rock the plane I finally understand why she asked. I’m rarely nauseous but the flight is testing. As we land 20 minutes later the pilot climbs out and heads to take the bags out from the luggage compartment. As he does he physically jumps into the air as a tarantula the size of your hand gets within a few inches of his foot. I can’t wait to get out and photograph it but before I can another man runs up and stamps on it. Such a shame, even in this pristine environment nothing is safe.

We then meet our new guide, Jonas, he’s quite the character and we get on immediately. He drives us to the camp through the only remaining village in the delta. It’s a small aggregation of people that didn’t want to leave when the government cleared all the settlements during the creation of the national park. Most of the buildings are made from mud, with their walls often supported with the help of old cans and bottles.

(A traditional Botswanan rondavel with cans used for reinforcement, Okavango Delta)

Our new camp, Moremi Crossings, is similar to the last, there’s not a hint of internet and it consists of raised safari tents looking out onto a stretch of water. Over dinner we get to know Jonas a bit more. He was born on a reed island in the far north of the delta when his mother went into labour unexpectedly whilst working. The first time he saw a car was in 1995, a Jeep that had made its way to the north of the delta. He was 11 years old and the only method of transport he’d ever seen or used was the Mokoro canoe. His English is impeccable, delivered with a calm demeanour that makes him easy and relaxing to talk with.

The next morning we head out early on a game drive. As the sun is rising we get sight of five lions not far from the camp, one of them, a young male, is digging madly in a hole to try and kill a warthog. Dust is flying out of the hole, a combination of the lion digging and the wart hog occasionally attacking the lion from inside. Eventually, the lion gives up and slumps down on a mound with his brothers in defeat. It’s a shame we didn’t get to see a kill, but I’m pleased for the warthog.

(Four juvenile male lions look for prey from a vantage point on a mound, Okavango Delta, Botswana)

We drive on, sometimes through water that comes up over the engine as we cross the various tributaries of the delta. Like most 4×4 vehicles in Africa we are in a Toyota, in this case a Land Cruiser. Jonas comments that when he has Japanese tourists they love the cars, chanting Toy-O-Ta as they drive through the deep water. Jonas does a very good impression that has us in stitches. He says they never chant Jonas, just Toyota. You can figure out what we chant for the next few days. As we proceed Jonas stops the car, opening his door and looking down. He says ‘female leopard, recent’ and crawls the vehicle slowly forward. He stops again. Jess looks up, and says ‘there’ and points into the tree above us. A male leopard is sitting with his legs hanging over both sides of a large branch, his half devoured prey is slightly further down in the Y of an Iron Wood tree. With his long tail and lazy pose he looks like a ruthless version of Tigger from Winnie the Pooh. It’s also the first time Jess or I have actually spotted a leopard first in all the safaris we’ve done so far. I’m strangely proud of her as we sit and enjoy the sight for an hour as the leopard shows little interest, sleeping and occasionally raising his head to investigate. What happened to the female leopard we were originally tracking remains a mystery, it appears to have been complete coincidence.

(A male leopard lounges in an iron wood tree, Okavango Delta, Botswana)

We drive on and Jonas takes us to a site where he saw some young lion cubs and their mothers a few days ago. We get lucky and find them at the edge of some tall grasses. The four cubs are play fighting, rolling around and feeding. Jonas explains that one cub was killed last week by the father because it tried to play with his testicles. Jess says she’d cut his testicles off if he did that to her child. It’s good to know. After another hour watching the cubs we drive back towards the camp but are suddenly stopped by two screeching honey badgers, one of them spitting formic acid at the bonnet of the Land Cruiser. It stinks as we drive past. I can understand why these small animals have a reputation for being ferocious and fearless. That evening we do a short night drive where we manage to spot a serval, more genets and a side striped jackal for the first time.

(A Lion cubs sit with their mother after feeding, Okavango Delta, Botswana)

(A damp and angry honey badger scurries for cover, Okavango Delta, Botswana)

After four days in the delta with early starts and long days in the car I am utterly exhausted. I also haven’t slept well due to the eco-lodges not having any air conditioning, and I have noticed a subtle paranoia is creeping up on me. It’s caused by the anti-malarial drug Lariam (mefloquine) that I am taking. I would have taken the more common Malarone but I had a reaction to it when I was younger which meant I couldn’t go out in the sun, so Larium is the less than ideal alternative. I’m also not sleeping well because the animals aggregate under your raised tent at night to avoid predators. Their grunts and whoops make for a disturbed, albeit entertaining, nights sleep. As we wake for the last day I’m completely shattered. We fly back to Maun and I can’t even bring myself to drive us to our next accommodation, Jess has to do the drive as I try to rehydrate and get some sleep.

Our time in the delta was simply amazing. Exhausting, but amazing. One of the best experiences in our travels in Africa. The low level of vehicles and the challenge of getting into the region make it a delight to visit. The wildlife is unspoilt and all animals seem healthy. The fur on all the cats we saw was glossy and full, even the hyenas looked fat. In one field of view we could see eight elephants, four cheetahs, zebra, topi and giraffe, the density of wildlife is higher than anything else we’ve seen. It’s also strange to reflect on our time spent with the guides. The amount of time spent in close proximity creates a bond over a relatively short period of time. On reflection, travelling is a series of these brief bonds, moments shared and memories created for both sides. As we hop our way from place to place you meet people that teach you things, insights you’d never considered and learn from their perspectives and by observing their different ways of life. I’ll always remember my time in the delta and I think the memories of the brief friendships formed will last as long as those of the wildlife.

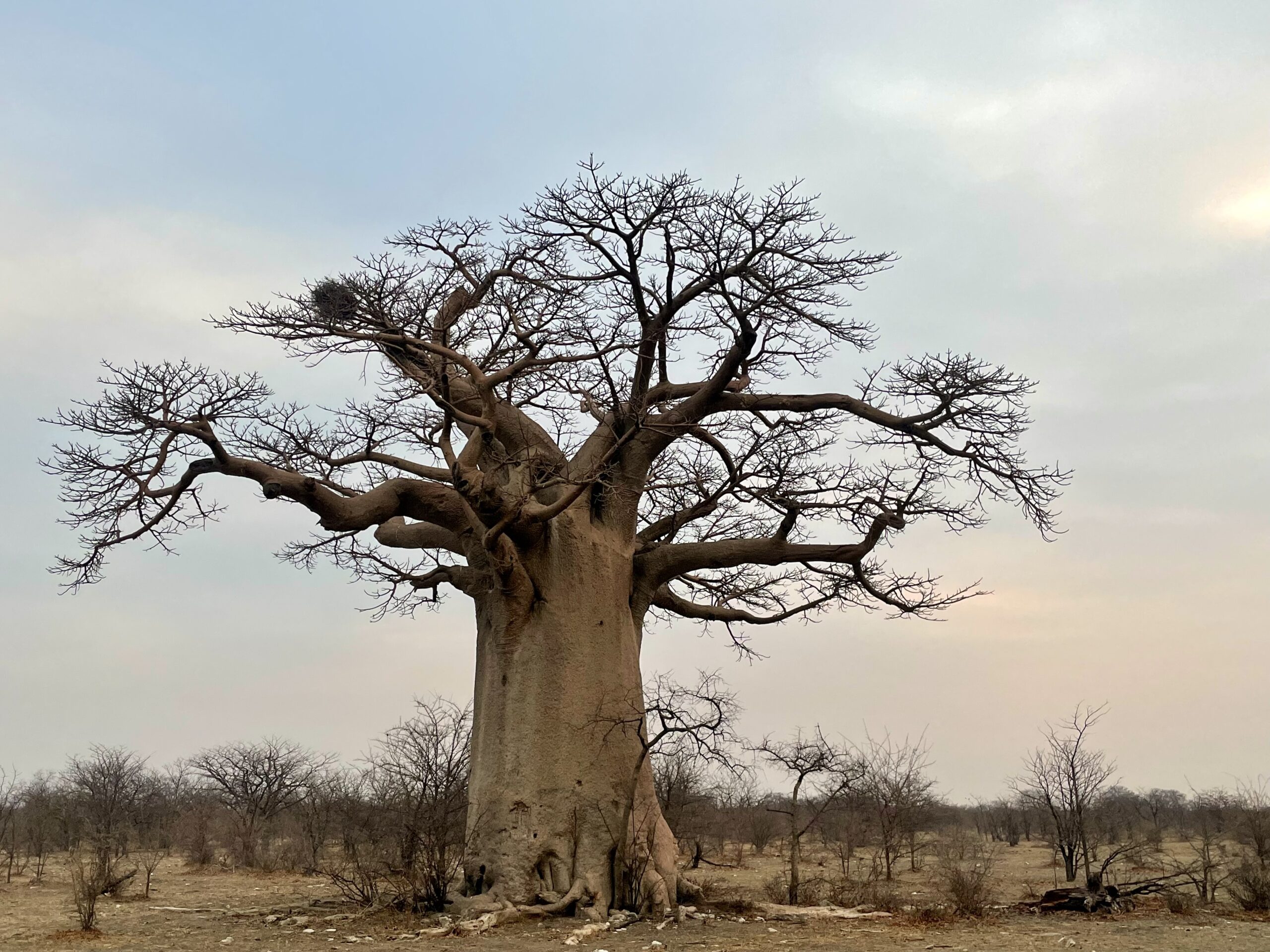

After the delta we drive towards the Makgadikadi national park, a salt pan the size of Switzerland. On the way we see about 100 elephants by the roadside, most of them grouped around concrete drainage water channels. They’ve smashed them open with their feet and tusks, the shattered chunks of concrete lying around each drain. As we pass through a particularly large herd we notice two cyclists have stopped up ahead. They flag us down and ask if we can escort them back along the road because some of the elephants have been quite aggressive. They cycle alongside the car chatting until we pass the herd and then we head back the same way we came. We drive on until we reach a small hotel in a Baobab forest where some of the trees (technically succulents) are more than 2000 years old.

(A large baobab tree, at least a few thousand years old, near the Makgadikgadi salt pan, Botswana)

The next morning we pick up some quad bikes to head into the salt flat itself. After half an hour on the bikes we stop and visit a family of habituated meerkats. As you bend down to take photos some of them take advantage of the apparent new vantage point and climb up and stand on your head to survey the landscape. As one looks out from on top of my cap it starts to squawk and all the surrounding meerkats stand to attention. The one on my head has spotted a dog in the distance. They all gather and the young head for the burrows. We head back to the quad bikes and make for the salt flat. The heat is rising from the pan and it shimmers as we drive along, stopping briefly for pictures before returning to our hotel.

(A meerkat seeks a vantage point on Jess’ head, Makgadikgadi salt pan, Botswana)

(Jumping for joy in the Makgadikgadi salt flat, Botswana)

Our final stop in Botswana is Elephant Sands, a hotel built around what was originally a natural waterhole in the northeast of the country. The waterhole has dried up a few times in dry season and so the hotel now tops it up on occasion. The impact of this on the local elephant population is hard to tell. Some are critical of it because it allows a population to survive in a location that becomes entirely dependent on human intervention. The elephants would have been forced to migrate, or worse perhaps died, if the water hole was not refilled. But, of course, this is business, so we get to enjoy 29 elephants drinking less than 10 metres away over dinner. They jostle for position, trumpeting loudly in objection as others try to move in. It’s a great end to the trip as we head north towards Zimbabwe.

Our time in Botswana has included some of the most amazing moments of our 3 months in Africa. I would conclude that the Okavango Delta was the best safari location on our African travels, but also by far the most expensive, with the 5 day trip into the delta costing around $5,000 USD. It’s pretty pricey compared to the self drive entry cost of $6 for Etosha National Park in Namibia. But, if you were only ever going to do one safari in your life it would be worth the cost. You can also do cheaper ones that drive to camps on the outer edges of the delta rather than flying in, I’d expect the wildlife would be similar. The country itself is fairly empty, around 5 people per km/square, only just above that of Namibia. As such, bustling African culture is not easy to come by and you can drive hundreds of kilometres without seeing another human. It truly must be one of the last wild places on earth, where nature runs the show and humans are lucky to visit.

(A Bateleur Eagle enjoys the sunset in a tree, Okavango Delta, Botswana)

(Top image: A young lion cub stares to camera, Okavango Delta, Botswana)